Reflection Of Olympos: Nature, Architecture, and the Living Landscape of Antalya

- Nov 17, 2025

- 7 min read

I love wandering through the ancient cities of Antalya — places like Olympos or Phaselis, where nature is reflected in its most beautiful form through ancient architecture. The Corinthian columns, with their carved acanthus leaves and spiraling vines, always strike me as proof that ancient builders were in dialogue with the natural world. These motifs weren’t simply decoration; they show an admiration, even an alignment, with the landscape around them. They also remind me how much craftsmanship was valued in ancient times, a level of artistry we rarely encounter in architecture today. When I was studying archaeology, my ancient Greek language teacher once told me that these architectural elements — the flowers, the leaves, even the statues — were originally painted in vivid colors. However, I liked them elegant in their bare stone form.

Vitruvius, Roman architect and architecture historian, tells us that the Corinthian capital was inspired by a basket left on a young girl’s grave, around which acanthus leaves grew and wrapped.

In the Lycian coastal cities of western Turkey, I sense a deep relationship between landscape and architecture. In Bodrum, the drier landscape seems to echo in the simplicity of Doric order — the earliest Greek architectural style, born in mainland Greece and later spread through the Greek colonies across the Aegean, Today’s Turkey.

The Greeks influenced the Lycian cities in western Antalya, blending their temples, inscriptions, and artistic styles with the local culture. Cities like Olympos, a member of the Lycian League, illustrate this fusion beautifully: Lycian in origin, yet shaped by Greek and later Roman architecture, Olympos held political importance as one of the cities with voting rights in the Lycian League (a union of cities much like the EU), sending representatives to decide on matters of regional governance. This shows how landscape, culture, and civic life were deeply intertwined.

The patches of lush forests are reflected in the ornate details of the ancient ruins of Antalya. Each region has its own energy — Lycian cities of Antalya vs. Halikarnasos of Bodrum — and traveling between these places — watching the dry land soften into forests as I approach Antalya — feels like witnessing the country’s emotional map.

These landscapes make me think of my grandmother, how she could look at anything — a tree, a stone, a bird — and see God working through it. Maybe that’s what I feel too, especially in the forests here. I have moments where I sense everything at once: the birds, the trees, the water, the unseen life. It’s like I’m feeling through the world, not just walking in it.

A year ago in Olympos, that feeling became especially strong as I climbed the steep path to the castle ruins. When I reached the top, the whole coastline opened in front of me, mountains descending into the sea, people swimming in the crystal clear waters. For a moment, I felt as if I were watching myself from outside, as if all those people were me and I was them. I love how this castle can give me the experience of oneness and separateness simultaneously.

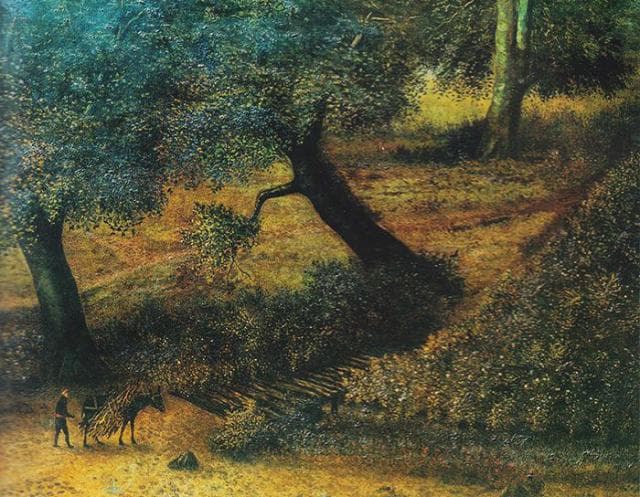

Being able to look at myself from above with an eagle-eye perspective reminded me of Şeker Ahmet Paşa’s Woodcutter painting, which John Berger described as giving the sense that the forest is swallowing the woodcutter. The painting’s intentional “perspective mistake” enlarges the forest and diminishes the figure, creating a view almost as if seen from above, emphasizing the greatness of the forest. In Olympos, I felt something similar: the ruins below me, the shoreline, the sea — everything felt connected, as if I was both inside the landscape and observing it from above.

After the hike, I dipped my feet into the cold water. Then I found a tree where this ancient stream runs under, still to this day, bringing running water to the ancient city. The feeling is so very strong, you can sense that the stream is part of this ancient city or the city is part of the stream.

Archeologist Nevzat Çevik writes in THE BOOK OF LYCİA about the city that: “The layout of the settlement is shaped by this stream, which flows through the middle of the city and dictated a plan unseen elsewhere in Lycia.” I climbed onto the tree and lay on its strong branches. From there, I could see the reflections of the water shimmering across its wide trunk. At first, I hesitated, if I could climb safely, but when I removed my shoes and left my backpack behind, I could climb better. Lying under a wide trunk of this tree made me feel the magic of this ancient forest. I soaked all the beauty and the magic in. When I was ready to keep moving forward. I realized my timing was perfect; as soon as I climbed down, I heard people approaching, as if the tree, this part of the forest was reserved for me for the time being.

The city asks me the question: “Do you have the courage to be shaped by your waters?” It makes me think yet again how art, architecture, myths were in reverence to the waters of the world, to the living world and not the other way around. Not like today how everything ugly is being built all around us. Somewhere along the way, we became estranged from nature, nature that governs life and death.

Back then architecture did not dominate the land; it listened to it. Today, the opposite is true. Cities are imposed on nature, and we live estranged from the rhythms that once held meaning. Perhaps this is why walking through Olympos feels like stepping into a memory not only of the ancient world, but of a human relationship to nature that we have almost forgotten how to speak about.

There is a tomb near the seaside, river-mouth entrance of Olympos, commonly referred to as the “harbour monumental tombs.” One of these tombs is attributed to a Captain Eudemos, whose sarcophagus displays in relief a ship. On top of the boat relief, there is a poem:

“The ship entered the last harbor and anchored to go no more, as there was no hope from neither the wind nor the daylight. After the light that bore the dawn had left, Captain Eudemos then buried the ship with a life as short as a day, like a broken wave.”

Standing before it, you feel how the people of Olympos understood the sea not only as the trading routes that sustained their livelihood, or the dangers of pirates, but as a metaphor for departure, return, and ending. A force woven into the rhythm of life and death, the river shaped the city and the sea shaped its stories. Death was seen not as rupture, but as coming to rest — a ship returning to its final harbor.

The path then took me to an old tomb — the tomb of Antimakhos — carved with a tree-of-life rising from a khantaros (ancient cup for drinking wine). This symbol represents the eternal cycle of life and death. Seeing it again felt like an echo of everything I had just experienced: the stream, the tree, the ruins, the feeling of being held by something larger, feeling the oneness while simultaneously feeling my being as separate from all, both being one with nature and moving through it.

I think I was able to receive all this beauty because I removed some kind of inner shield. My eyes were sparkling as the tears arrived from the sheer grace of this experience. The gift of being able to feel it all. Just before coming here, I worried that perhaps I had lost that ability forever. Yet being here once again, I was restored. All these different ancient cities of Antalya have different things to offer, and visiting them again and again feels holy. That day, in Olympos, surrounded by ruins, the stream and trees, I felt mesmerized again, felt like a blessing, a sign that something inside me was opening. I was finding my connection back to the living world after a season of endings.

Ever since I came here to Antalya, this place has always been very special for me, and the first thing I did moving here was to visit this place. After a year, back at the end of May, I visited this place again, and I even found my arm cuff there in a museum shop. Over the years, I have been brought back here time and time again, and it has its magic, and I am so grateful to be able to feel that.

Just like Çevik said in the preface of his book, I also feel like writing this post is ‘my way of repaying my personal debt to the region of Lycia’.