Sarajevo, the city where sorrow and hope meet

- Apr 7, 2023

- 5 min read

As I went for dinner with my colleagues in Sarajevo, the table was set, and shots of rakija were poured. Suddenly, a local would start singing, and though the songs sounded lively and energetic, deep down, I couldn't help but feel a sense of sorrow. I vividly remember one powerful moment at the restaurant Mala Avlija, when the music brought people together as the restaurant owner Asım led the crowd to sing.

When Asım played "Opa cupa," it was the first time I had heard the song. He brought a microphone so that others and he could sing along. As he sang, his gestures added a new layer of meaning to the music. One moment, he was fully immersed in the song, and the next, he leaned on a table, and took a breath from his cigarette, as if he was watching the happy people with sad eyes.

In Sarajevo, I was exposed to Sevdalinka, a traditional Bosnian-Herzegovinian folk music genre as well as gypsy songs. Gypsy songs seem to have a magical quality that captivates everyone and compels people to dance whereas the sensuality of Sevdalinka can make listeners feel like the main character of some sort of love novel as my Kosovian friend described her feelings raised by these songs.

Here are the songs, some of which I discovered during my visit to Sarajevo.

The first time I heard the name of the music genre Sevdalinka, I was surprised how this word came to be a folk song name in the Balkans. It almost sounded like a Turkish word to me. Sevda in Ottoman Turkish means love and the word derives from Arabic. Even though I knew that the Ottoman Empire ruled the country for almost four centuries. It was interesting to have a firsthand experience of how the culture and language had been influenced by the Ottomans. During my stay, I experienced the religious celebration of the Feast of the Sacrifice so-called Bayram (Eid al-Adha). I noticed that Bosnians congratulated each other on this religious day with a Turkish phrase "Bajram Šerif mubarek olsun".

Wandering through the city I couldn’t help but notice the bullet marks on the buildings and the gravestones near parks. Every corner of this city was pushing me to learn more about its history. Despite the city's scars, I felt like music stands for hope here. The music connected people in different settings.

Meeting point of three different religions

From the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on the Latin Bridge, a significant event that sparked the beginning of World War I, to the tragic burning of over two million books and documents by Serbian criminals in the city hall, the National Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in 1992. The city witnessed a lot of sorrowful historical events.

In the midst of this sorrow, Sarajevo also witnessed moments of hope. For me, the most interesting of them was the protection of Sarajevo Haggadah. The illuminated Jewish codex was protected by the Muslim community during the Nazi occupation of the city.

In 1941, when German authorities demanded the Haggadah from the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where it was stored at the time, the museum director handed it over the codex to Derviš Korkut, an Islamic scholar, and curator of the Museum. He took a serious risk to protect it. Korkut brought the Haggadah to the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque in Sarajevo. He handed the manuscript over to the mosque's imam, Hafiz Abdulah-efendija Bašić, who placed it in the mosque's library for safekeeping.

Although the mosque was repeatedly searched by the Nazis and their allies, The Haggadah remained hidden in the mosque throughout the war. Korkut and Bašić both risked their lives to protect the manuscript. The Sarajevo Haggadah was safely stored in a mosque until the end of the Second World War. After the war, the Haggadah was returned to the National Museum where it is on display today.

A Powerful Scene of Communal Prayer

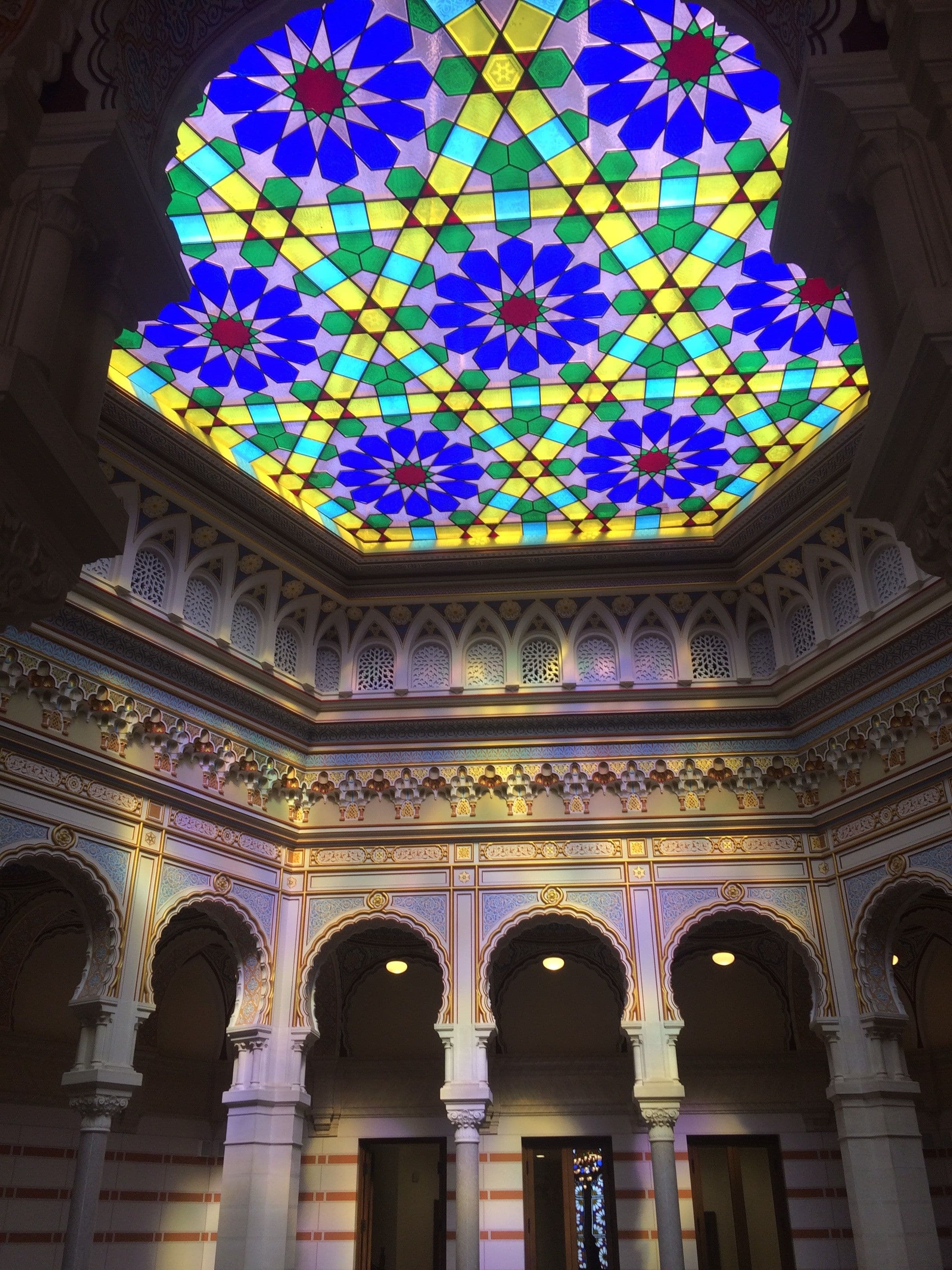

My friends and I strolled through Baščaršija after a satisfying dinner at Dveri. As I looked through the window of a Gazi Husrev-beg mosque one scene urgently caught my eye. In the mosque's garden, a group of people was performing the wudhu, the ritual ablution before prayer. It was an influential scene for me to witness, because in Turkey I haven’t seen men and women performing the wudhu together. The sight of individuals coming together to prepare for prayer was powerful and moving.

After watching them from the window for a while I felt a strong urge to immerse myself in the atmosphere. I entered the mosque's garden to experience the healing power of communal prayer. I enter the garden and stood there watching men and women praying outside of the mosque. The feeling of being part of something greater than myself was profound, and it left a lasting impression on me.

Although I had prayed in mosques when I was younger, I haven’t felt this kind of connection and appreciation. What might have truly influenced me in this scene was seeing a group of men and women separately praying on both sides of the mosque's door on the same level, as opposed to being too separated. Typically, women are confined to the upper floors of the mosque and must enter through a separate door, while men pray on the main floor.

This encounter inspired me to write a news story about women's experiences in mosques in Turkey.

Encounter with "Man of Sorrows"

As I wandered through the Old Orthodox Church Museum, my attention was drawn to an array of fascinating objects on display. From the opulent gold brocade vestments to the intricate church drapery, and the ornate metal crosses dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries, every item was a testament to the old history of Christianity. Amongst all of these treasures, however, it was one painting that truly captured my attention.

"Man of Sorrow," a portrait of Jesus, captured my gaze with its poignant depiction of anguish and suffering. It was as impressive as it was sorrowful. The painting was full of intricate details, revealing the artist's deep understanding of the agony.

I was struck by the universal nature of pain, a feeling that transcends time, culture, and religion. Whether we experience it ourselves or witness it in others, the anguish of suffering transcends all boundaries. The painting reminded me of the power of art that connects us to the human experience. The Old Orthodox Church Museum was a treasure trove of history and culture, but it was this painting that truly moved me.

The city of Sarajevo is a unique meeting point of three different religions, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, which have coexisted here for centuries, leaving their mark on the city's architecture, culture, and traditions.